Akiyoshi Mishima SASSURU (察する)

11/01/2014 – 25/01/2014

Eröffnung: Freitag, 10. Januar 2014, 19-22 Uhr

Akiyoshi Mishima

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„SASSURU (察する)“, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Tawaraya“, 2014

Lack auf Acryl

91 x 91 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Susanoo“, 2014

Lack auf Acryl

91 x 91 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Nobunaga“, 2014

Lack auf Acryl

91 x 91 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

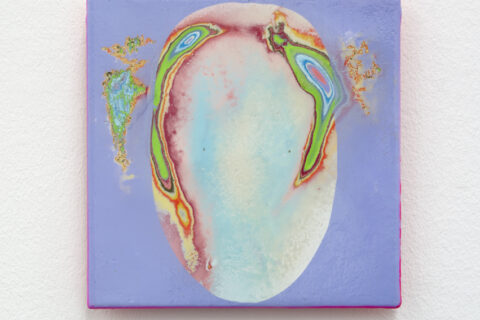

„Not such issue, 005“, 2013

Lacquer spray, ceramic

20 x 20 x 1,5 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Not such issue, 007“, 2013

Lacquer spray, ceramic

20 x 20 x 1,5 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Not such issue, 008, 2013

Lacquer spray, ceramic

20 x 20 x 1,5 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Not such issue, 004“, 2013

Lackspray, Keramik

20 x 20 x 1,5 cm

Photo: Simob Vogel

„Not such issue, 001“, 2013

Lackspray, Keramik

20 x 20 x 1,5 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„DY-15“, 2011

aluminium, synthetic resin paints

20 x 26 x 55 cm

„KO-17“, 2011

Aluminium, resin color

30 x 33 x 39 cm

„Clay Ship“, 2012

C-Print

300 x 120 cm

„Light. Stamp Clay“, 2012

Holz, lack, Ton

91 x 42 x 3 cm

Untitled, 2012

Metall, Lack

ca. 255 cm

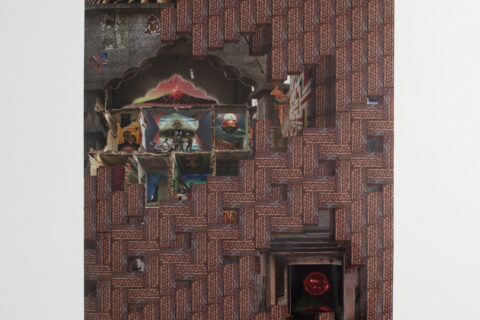

„Okazari“, 2013

C-Print, wooden box, clay, steel, lacquer

C-Print: 185 x 185 cm // 188 x 188 cm (framed)

Wooden box: 13 x 48 x 48 cm

„Zig-Zag“, 2013

C-Print, wooden box, clay, lacquer

C-Print: 127 x 127 cm // 130 x 130 cm (framed)

Wooden box: 7 x 39 x 33 cm

„Cairn“, 2013

C-Print, wooden box, clay, lacquer

C-Print: 127 x 127 cm // 130 x 130 cm (gerahmt)

Wooden box: 9 x 91 x 17 cm

Press Release

Für seine "Portraitserie" großer japanischer Meister besprüht Akiyoshi Mishima Plexiglasplatten mit bis zu 40-50 verschiedenen Lack Farbschichten, in die er die abstrahierte Gesichter einschleift. Er begibt sich dabei, nach Maßgabe des "Sassuru" (siehe unten) mit dem Kunstwerk in eine Art wechselseitigen Gestaltungsprozess.

Die in den Portraits dargestellten Meister sind (von rechts nach links):

- Tawaraya , Maler der Edo Zeit und Gründer der Rimpa Schule.

- Susanoo, in der japanischen Mythologie des Nihon Shoki ist er der Gott des Meeres.

- Nobunaga, ein berühmter Samurai.

Rikyuu, ein bedeutender Teemeister japanischen Sengoku-Zeit führt die Gäste der Teezeremonie in einen kleinen Raum, der auf harmonische Weise mit Kaligraphie Blumenkunst der Jahreszeiten ausgestattet ist. Diese dürfen nicht zu auffällig oder grell sein, denn die einzelnen Elemente gehören der Natur an, die quasi "natürlich" die Jahreszeiten in den Raum bringt. Das so mit der Natur harmonische Ambiente gilt als Spiegelbild des Inneren (des "Herzens") des Gastgebers, das die Gäste in sich aufnimmt. Zwischen den beiden werden keine Floskeln des Lobs oder Worte der Erklärung gewechselt. Der Gastgeber weiß, dass seine Gäste bereit und fähig sind, seine Herzlichkeit und Gastfreundschaft, die durch die miniaturisierte Natur des Raums ausgedrückt ist, zu lesen und in Empfang zu nehmen. Diese organische Art des gegenseitigen Verstehens und des Dialogs ohne Worte nennt man im Japanischen "Sassuru". Es ist in vielen alltäglichen Abläufen präsent.

Auf ähnliche Weise verfährt ein Töpfer, indem er die einzelnen und einzigartigen Phänomene, die sein Werk bestimmen, entdeckt und versteht. Sie gelten ihm als durch Feuer oder Asche oder Luft "zufällig" entstanden. Im Dialog mit seinen Werken liest er heraus, was ihm deren feine Details sagen. Dabei spielt nicht nur das Kriterium der Schönheit, sondern auch andere Qualitäten wie z.B. spielerischer Humor eine Rolle. Sie bilden für ihn dann das Wertvolle seiner Arbeit.

Eine derart "offene" Haltung versucht Akiyoshi Mishima gegenüber seinen Arbeiten einzu-nehmen. Beim Schleifen der vielmals mit bunten Lacken beschichteten Oberflächen spielt Zufall eine Große Rolle. Im Arbeitsprozess tritt Mishima mit seinen Bildern in einen Dialog, in dem schließlich die Bilder ihm zeigen, wie er weiter vorzugehen hat. Auf diese Art und Weise lässt die Arbeit den Künstler entstehen und nicht umgekehrt. Erst nach diesem sich vielfach wiederholenden Prozess entsteht ein vollständiges Kunstwerk.

----------

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (俵屋 宗達?, fl. early 17th century) was a Japanese artist and also the co-founder of the Rimpa school of Japanese painting. Sōtatsu began to work as a fan-painter in Kyoto. Later, he rose to work for the court as a producer of fine decorated papers for calligraphy. He was highly influenced by Kyoto’s courtly culture. Sōtatsu met the great designer and calligrapher Hon'ami Koetsu, and painted under-designs in gold and silver for his writing. Sōtatsu excelled in projects that needed careful placing of decorative screens and fans, and took this to its highest level. He pioneered a new boldness of color and line. He popularized a technique called tarashikomi, which was carried out by dropping one color onto another while the first was still wet. Sōtatsu also developed an original style of monochrome painting, where the ink was used sensuously, as if it were color. Among his best works are the illustrated covers he painted for the Lotus Sutra.

Rinpa (琳派 Rinpa), is one of the major historical schools of Japanese painting. It was created in 17th century Kyoto by Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and Tawaraya Sōtatsu (d. c.1643). Roughly fifty years later, the style was consolidated by brothers Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743).

The Nihon Shoki (日本書紀?), sometimes translated as The Chronicles of Japan, is the second oldest book of classical Japanese history. The book is also called the Nihongi (日本紀 lit. Japanese Chronicles?). It is more elaborate and detailed than the Kojiki, the oldest, and has proven to be an important tool for historians and archaeologists as it includes the most complete extant historical record of ancient Japan. The Nihon Shoki was finished in 720 under the editorial supervision of Prince Toneri and with the assistance of Ō no Yasumaro.

The Nihon Shoki begins with the Japanese creation myth, explaining the origin of the world and the first seven generations of divine beings (starting with Kunitokotachi), and goes on with a number of myths as does the Kojiki, but continues its account through to events of the 8th century. It is believed to record accurately the latter reigns of Emperor Tenji, Emperor Temmu and Empress Jitō. The Nihon Shoki focuses on the merits of the virtuous rulers as well as the errors of the bad rulers. It describes episodes from mythological eras and diplomatic contacts with other countries. The Nihon Shoki was written in classical Chinese, as was common for official documents at that time. The Kojiki, on the other hand, is written in a combination of Chinese and phonetic transcription of Japanese (primarily for names and songs). The Nihon Shoki also contains numerous transliteration notes telling the reader how words were pronounced in Japanese. Collectively, the stories in this book and the Kojiki are referred to as the Kiki stories.

Oda Nobunaga was born on June 23, 1534, and was given the childhood name of Kippōshi (吉法師?). He was the second son of Oda Nobuhide. Through his childhood and early teenage years, he was well known for his bizarre behavior and received the name of Owari no Ōutsuke (尾張の大うつけ?, The Fool of Owari). With the introduction of firearms into Japan, though, he became known for his fondness of tanegashima firearms. He was also known to run around with other youths from the area, without any regard to his own rank in society. He is said to be born in Nagoya Castle, although this is subject to debate. It is however certain that he was born in the Owari domain. In 1574 Nobunaga accepted the title of kuge (court noble), then in 1577 he was given the title of udaijin (or Minister of the Right), the third highest position in the Imperial court.

Die Sengoku-Zeit (jap. 戦国時代 sengoku-jidai, dt. Zeit der [gegeneinander] kriegführenden Lande) ist eines der bewegtesten Zeitalter in der japanischen Geschichte. Der Beginn der Sengoku-Zeit wird auf etwa 1477 (Ōnin-Krieg) auf das Ende des Ashikaga-Shōgunats datiert. Die Sengoku-Zeit ging 1573 in die Epoche der drei Reichseiniger (Azuchi-Momoyama-Zeit