Christian Kosmas Mayer paelis

14/06/2014 – 26/07/2014

Eröffnung: Freitag, 13. Juni 2014, 19-22 Uhr

Opening: Friday, June 13th, 2014, 7-10 pm

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Piloten“, 2014

3 Kieferstämme (Alter ca. 400 Jahre, zwischen 1710 und 2012 als Stützpfeiler unter dem Berliner Stadtschloß verwendet), Bienenwachs 592 x 40 cm, 656 x 30 cm und 645 x 33 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Piloten“, 2014

3 Kieferstämme (Alter ca. 400 Jahre, zwischen 1710 und 2012 als Stützpfeiler unter dem Berliner Stadtschloß verwendet), Bienenwachs 592 x 40 cm, 656 x 30 cm und 645 x 33 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

“paelis”, 2014

Installationsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

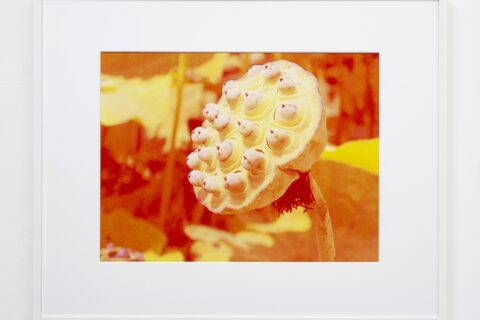

„Holy Lotus“, 2014

Dye Transfer (Cyan/Magenta, Cyan/Yellow, Magenta/Yellow)

je 38 x 52 cm (ungerahmt) / 63 x 78 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

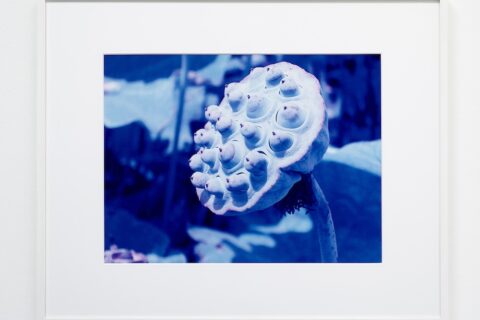

„Holy Lotus“, 2014

Dye Transfer (Cyan/Magenta, Cyan/Yellow, Magenta/Yellow)

je 38 x 52 cm (ungerahmt) / 63 x 78 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Pilot“, 2014

Kieferstamm (Alter ca. 400 Jahre, zwischen 1710 und 2012 als Stützpfeiler unter dem Berliner Stadtschloß verwendet), Schellack

339 x 33 cm and 347 x 32 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Pilot“, 2014

Kieferstamm (Alter ca. 400 Jahre, zwischen 1710 und 2012 als Stützpfeiler unter dem Berliner Stadtschloß verwendet), Schellack

339 x 33 cm and 347 x 32 cm

Foto: Simon Vogel

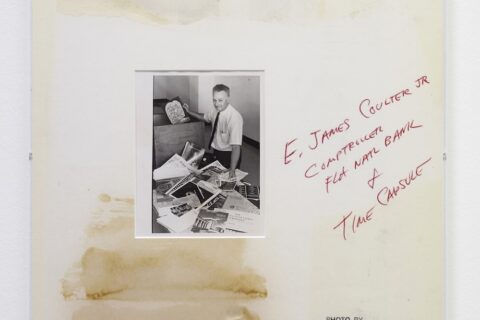

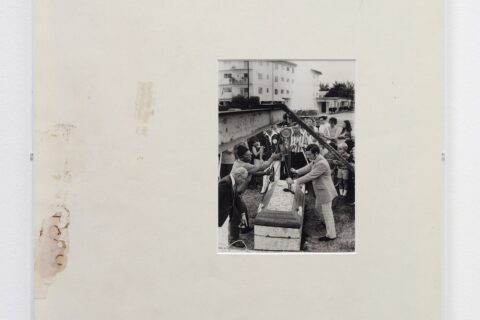

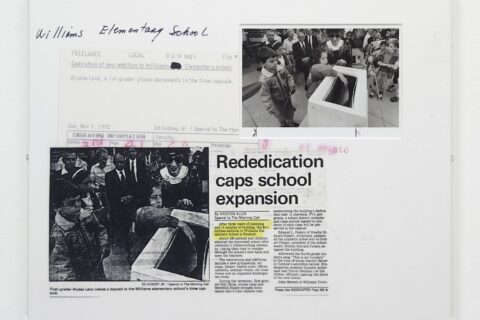

„Putting in time (06/89)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

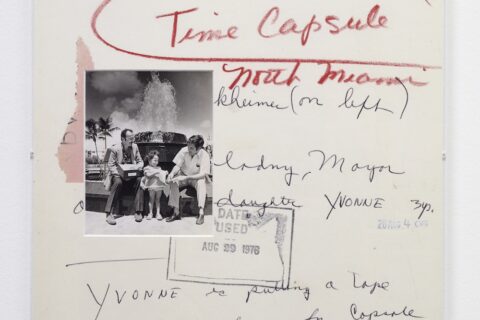

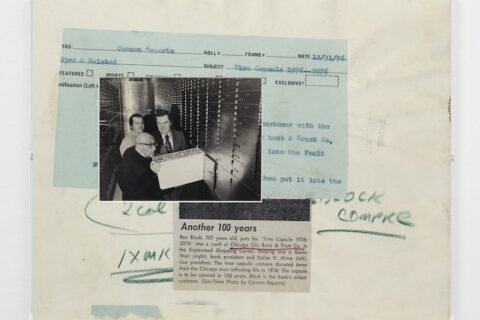

„Putting in time (12/22/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

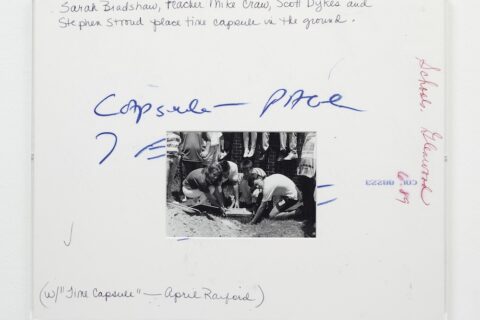

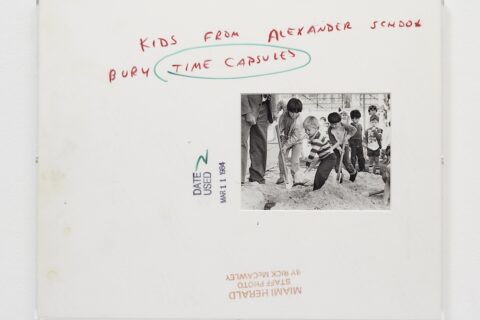

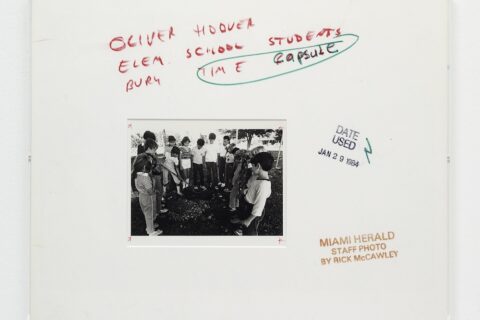

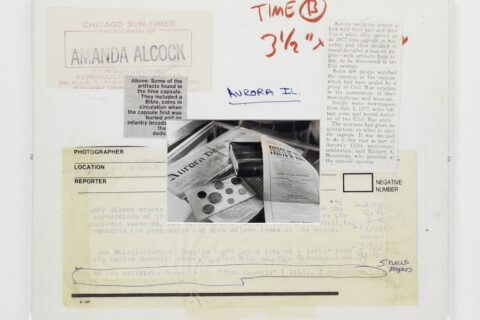

„Putting in time (03/11/84)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (11/11/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (01/29/84)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

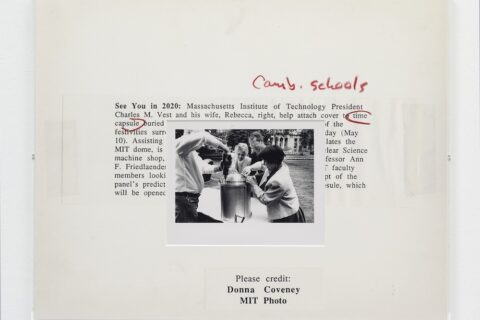

„Putting in time (05/10/91)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

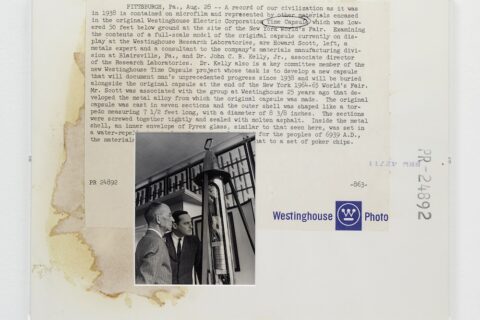

„Putting in time (08/28/63)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

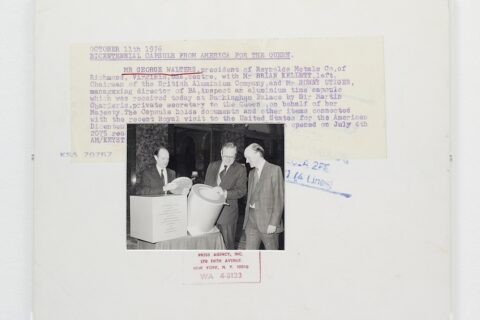

„Putting in time (10/11/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (04/17/85)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

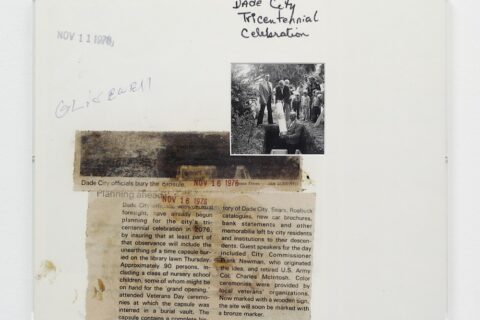

„Putting in time (11/16/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (08/05/90)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

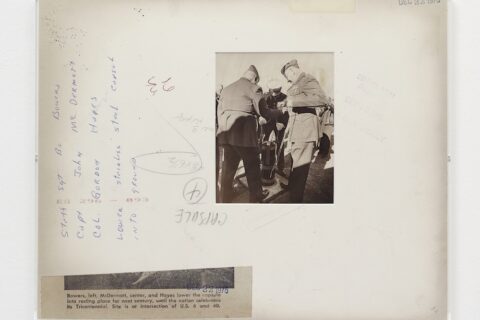

„Putting in time (07/24/41)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (02/27/83)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (11/21/68)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (12/16/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

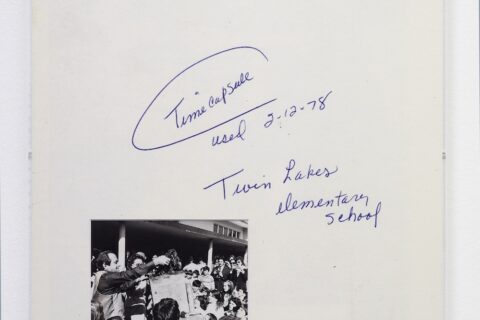

„Putting in time (02/12/78)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

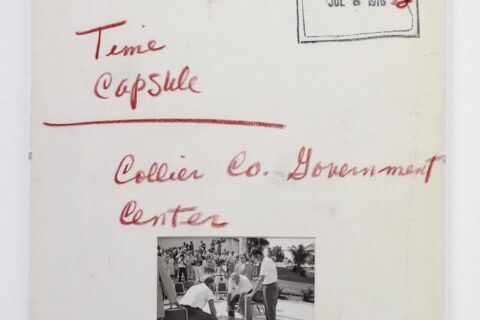

„Putting in time (07/08/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

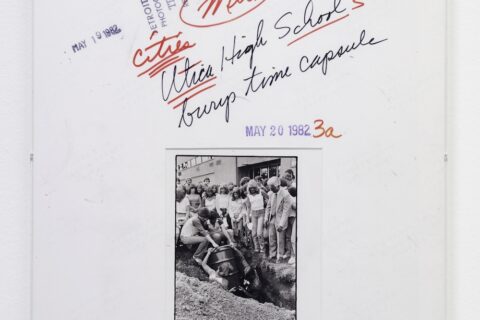

„Putting in time (05/19/82)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

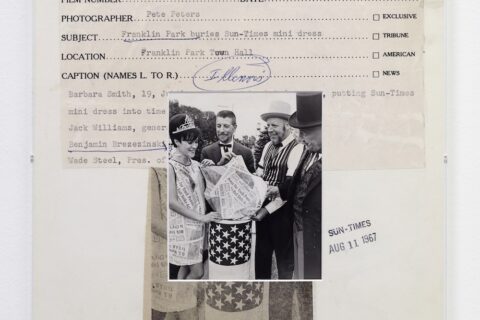

„Putting in time (08/09/67)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Holy Lotus“, 2014

Dye Transfer (Magenta/Yellow)

je 38 x 52 cm (ungerahmt) / 63 x 78 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Holy Lotus“, 2014

Dye Transfer (Cyan/Magenta)

38 x 52 cm (ungerahmt) / 63 x 78 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Holy Lotus“, 2014

Dye Transfer (Cyan/Yellow)

38 x 52 cm (ungerahmt) / 63 x 78 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

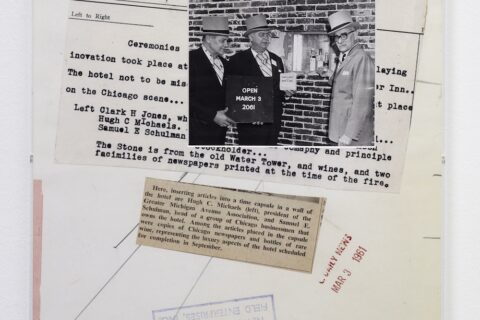

„Putting in time (03/03/61)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

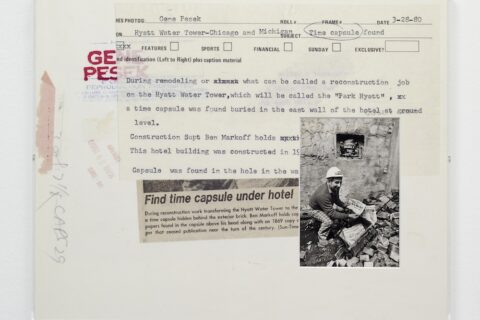

„Putting in time (03/28/80)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

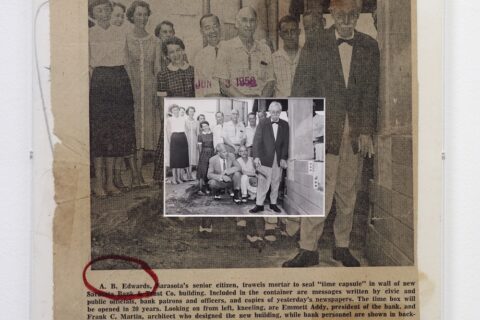

„Putting in time (06/03/58)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

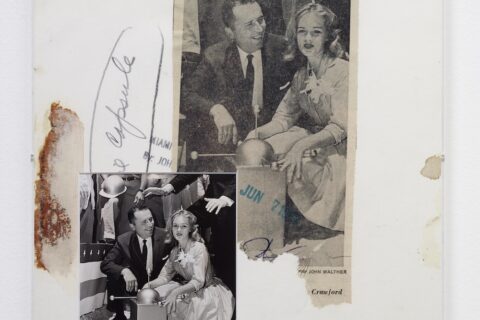

„Putting in time (06/07/62)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

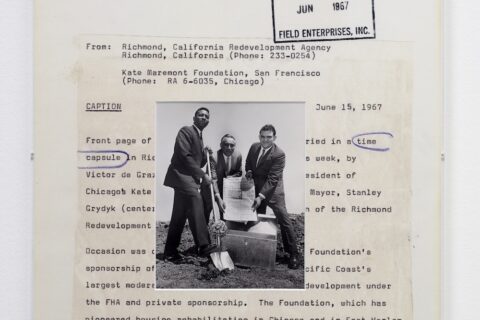

„Putting in time (06/15/67)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (08/04/92)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (08/28/76)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (08/31/87)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

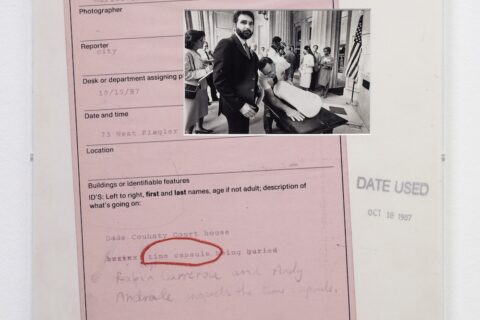

„Putting in time (10/16/87)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

66 x 53 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (11/01/1992)“, 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Putting in time (12/31/76),“ 2014

Originales Pressefoto aus Zeitungsarchiv, UV Druck auf Passepartout, Acrylglasrahmen

53 x 66 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Three of Diamonds“, 2014

HD Video, 12 Min

Press Release

He believed in an infinite series of times, in a growing dizzying net of divergent, convergent, and parallel times.

From Borges’s “The Garden of Forking Paths”

Memories are the representation of something that is no longer there, like someone’s memory of how the bronze mirrored windows of the Palast der Republik looked on April 23, 1976. But we often need triggers or clues to recall how something looked or to remember some fact or detail; we often need what Pierre Nora has called lieux de mémoire. Places that remind us of the past, like monuments, museums, and even art history itself, are lieux de mémoire—they are monadic and have no referent in reality; they are regarded as part of the past. The Berliner Stadtschloss, the royal palace of Berlin that once stood where the Palast der Republik was later built, is part of the past. The sharpened pine piles that were driven into the soft Berlin earth around 1700 to help support the Stadtschloss are part of the past. Buried and forgotten, they endured time until they were unearthed 2 years ago, and are now exhibiting their preserved core. Mayer has sawed off one end of each of the nearly four hundred-year-old trees and applied beeswax to the newly revealed parts, allowing you to walk through the years, ring by ring, and call to mind the memories stored and hidden in these piles—Kings of Prussia, world wars, the GDR, and German reunification. The almost seven meter-long sculptures that Mayer has made of these trees are a sort of unearthed time capsules. In this space, however, Piloten become much more—they become representations of what our memories may be in the future, they mix with the past and present and fork into the future by forming new bases on which we can form new memories.

These former foundations no longer stabilize anything. Rather, these sculptures are now part of what might be called milieux de mémoire, to again borrow a term of Nora’s. Milieux de mémoire are settings where memory is part of everyday lived experience, and are a communally accessible part of public life. Such milieux function through family resemblances, through a network of associations—like many of the pieces in Mayer’s exhibition. The photograph series called Holy Lotus, for example, continues the artist’s two-dimensional investigation into the idea of recovery. In his new photographs, Mayer shows an image of an ancient Lotus plant that was grown in a Californian laboratory from seeds that were unearthed at the site of a former lake in Liaoning Province, China. This lake dried up due to an earthquake in the region in the sixteenth century and the plant seeds were encased in the ground—at about the same time the pine trees used as support for the Stadtschloss began to grow near Berlin. A plant recouped from lost time can be grown today, and Mayer’s photographic prints take the idea of regaining one step further by using a dye transfer process to create the works—an almost forgotten process that delivers the best in longevity—that will be around to cue future memories. But in a spin to be found in other aspects of his work, Mayer layers the psychological and very real pitfalls of memory into his artistic process, for he has only combined two of the three available color layers (Cyan/Magenta, Cyan/Yellow, Magenta/Yellow), creating three different versions of the same picture. This decision and process will affect the future memories we have of this work, and relates to the synthetic nature of the plant growing in a lab.

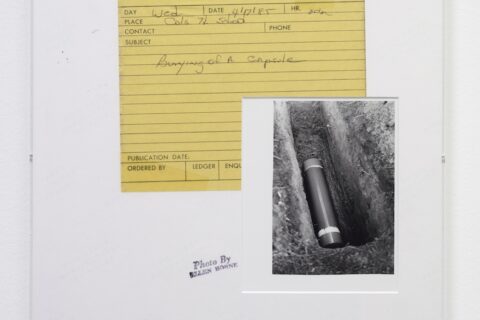

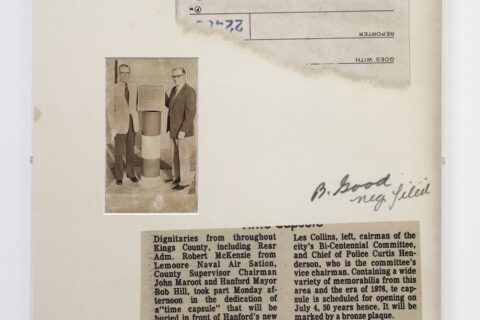

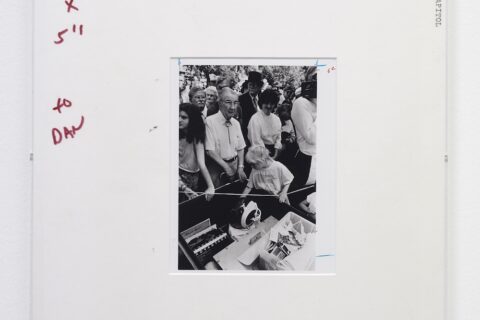

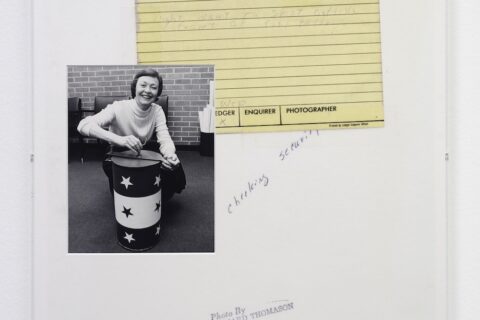

In another work that shows Mayer’s interest in pictures that have lost their original context, Putting in time exhibits original analog pictures from the archives of American newspapers that are framed by enlarged reproductions of the backs of these pictures, which, perhaps playfully, let us see the notes and marks of the time (handwritten annotations, stamps, etc.). The photos themselves document the burying or unsealing of time capsules and thereby the human attempt to contain the present, albeit for the future.

I think Mayer’s show presents us with a milieu de mémoire, where we can integrate the past into the present. But it is his video, which adds a twist to this installation by showing someone—an Austrian Champion of Memory—actively constructing a “memory palace” in the present in order to remember the order of a whole deck of cards. By using this ancient mnemonic technique he is literally building an internal place for his memories based on the foundations of his past (in this case his former school building), where he can saunter through its corridors and access the information by accessing the strange little scenes that he has stored there. The allusion to the City of Berlin building a new Stadtschloss on the same spot as the old building is hard to miss, and I think the video adds an ethical dimension to Mayer’s queries into memory and time. The work, and indeed the whole constellation of works, can be read as wondering what should or can be remembered. What does time erode? What can we build on top of our memories to make foundations for future memories? In other words, paelis is an active aesthetic site that can facilitate our viewing the past as part of the present, creating a continuum of times, and proving William Faulkner’s oft-quoted line: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

The twist that his video adds can also be found in Mayer’s very artistic methodology: investigating in an aesthetic way recovery, memory, continuation, and, above all, the nature of time. How does time create something new from something old, and how do we relate to this state of being? Heady questions, but ones that find themselves addressed in an open way in Mayer’s work, true to the nature of milieux de mémoire. In looking at and thinking about Mayer’s work, I recalled Jorge Luis Borges’s story “The Garden of Forking Paths,” in which the narrator learns of an ancestor’s mysterious novel and attempt to build an infinite labyrinth. No great novel and no labyrinth was ever found, so the narrator is surprised when he meets a stranger in the garden of forking paths who tells him the secret of the novel and the maze: the novel and the labyrinth are one and the same. The nonsensical novel advances the idea of branching, non-linear time, where multiple outcomes are possible, like an endless maze. Much of this brilliant short story is a spatial metaphor for time, and so too is Mayer’s exhibition, though an artistic metaphor. After all, as the great mnemonists have taught us, it is often images through which we remember best.

—Aaron Bogart