Paul Seidler Nightmarket

21/02/2026 – 18/04/2026

Nagel Draxler Kabinett

Rosa-Luxemburg-Straße 33

10178 Berlin

Opening / Eröffnung:

Freitag, Februar 20, 2026, 17 – 20 Uhr

Friday, February 20, 2026, 5 – 8pm

Öffnungszeiten / Opening hours:

Dienstag - Freitag 11 – 18 Uhr, Samstag 12 – 18 Uhr

Tuesday - Friday 11am – 6pm, Saturday 12 – 6pm

Press Release

View: according to which any artistic theory functions as an advertisement for the artistic product, whereas the artistic product functions as an advertisement for the powers under which it was born. (Marcel Broodthaers, Interfunktionen, No. 11)

Historically, Nightmarkets can be traced to the medieval Tang Dynasty China (618–907 AD), first appearing as an alternative to the older market system called the fāngshì zhì (坊市制), or ward-and-market system. State-sanctioned markets and commerce was only permitted by day, while at night access to the streets was heavily regulated, with guards stationed at junctions enforcing compliance. Nightmarkets were, in a sense, one of the first cracks in that system, emerging as forms of trade and commerce that escaped the formal, state-designated market. The earliest Nightmarkets were primarily informal venues for nighttime grain trading to accommodate farmers and laborers after daytime agricultural work. While daytime imperial markets were reserved for official transactions, Nightmarkets catered to commoners seeking readily available, affordable goods – a parallel economy for people the formal system didn't serve.

The art market, and more specifically the digital art market – as the various places where artists, gallery owners, and buyers come together – can be described as an “informal market” (Graw 2008, 66). Informal markets often exhibit characteristics that correspond to the precarious economic conditions of art production. However, with the emergence of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), it became apparent that the overriding logic of traditional art markets was not wholly compatible with digital works. As a result, the primary and secondary markets for contemporary digital art differ fundamentally in structure from established art markets. In its infancy, the price and volume of primary sales of NFTs were too low to be of interest to commercial enterprises. During this period, artists typically created their own bespoke interfaces, tooling and websites where buyers could purchase and mint their NFTs. These early forms established a small but significant alternative to the gallery system for digital works, forging parallel distribution mechanisms and channels while enabling new spaces for critical discourse.

While primary sales of digital artworks integrating with NFTs remained economically marginal, especially in the formative stages, the majority of profits accumulated through resale on secondary markets. This 'primitive accumulation' culminated in what was essentially a market monopoly by OpenSea (the largest NFT marketplace), which persisted for several years. OpenSea placed considerable stress on artists, as their work was subjected to a 24-hour buy-and-sell logic – every piece accompanied by a real-time price feed and publicly visible analytics. Unlike traditional art markets, where prices remain opaque, negotiated privately, or revealed only at auction, OpenSea's interface transformed every artwork into a constantly fluctuating financial ticker – a permanent stock exchange where aesthetic value became indistinguishable from speculative volatility.

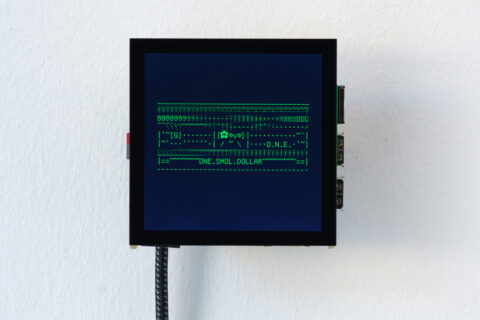

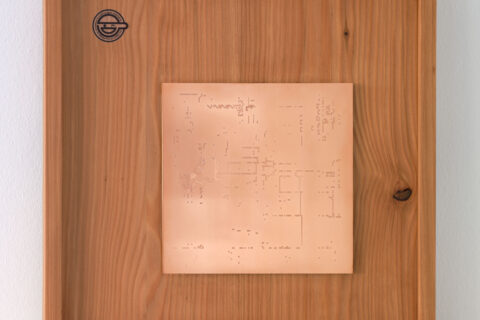

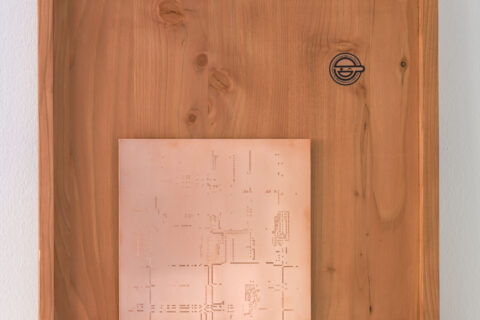

Smol Dollar is a work that confronts these conditions, consisting of an NFT series of 545 animated ASCII Dollar bills embedded in a system of smart contracts that, similar to a central bank (or a blue-chip gallery), supports the price of each individual Smol Dollar. This works as follows: 50% of the initial purchase price of each Smol Dollar is held by the smart contract in a decentralized Ethereum internal financial instrument (STETH), which emits ~2% per year in “profit.” The smart contract acts as a “market maker of last resort,” taking on the function of a bank to which the individual Smol Dollar can be redeemed again and again. This creates a slowly rising price corridor – a structure that lays bare the fragile separation between art and investment, exposing the asset and distribution logic that conventional art markets leave unspoken. The work can certainly be understood as an echo of works such as Les Levine's Profit Systems I or Robert Morris Money, 1969–73, but the location appears to be different: while Morris's work is quasi-embedded in the institution itself, Smol Dollar is infrastructurally autonomous. The artwork follows the secret but never spoken aloud dream of 1970s conceptual art’s dematerialization (Cras 2018): to become exchange value without use value, pure and bound to the commodity of money.

As Deleuze and Guattari suggest, every deterritorialization is followed by a reterritorialization, establishing new modes of control. From this emerges a type of 'protocol art,' in which the rules of interaction and the grammar of code are inherent to the medium – a line of flight along which the strict distinction between the 'ideal' work of art and the work of art as a commodity begins to crumble. This can be understood as a twofold escalating crisis logic and its reaction: a reaction initiated by artists to a more comprehensive crisis in art itself, as well as a monopolization of the digital art market, in which a parallel structure for interaction, distribution, production, and discourse is constructed out of necessity.

The contradictions of the commodity form are magnified in NFTs: the commodity, as a form inherent to capitalism, constantly reproduces historically conditioned social values. Karl Reitter points to these intrinsic qualities: "The commodity form is therefore capitalism's most stubborn and powerful bulwark against its own overcoming. But it contains qualities and quantities that do not correspond to the form and are not determined by this form“(Reitter 2011, 67, translated by the author). The crisis logic of the art markets follows this overdetermination of the ”cellular form” (Marx 1962, 12) of capitalism even more intensely.

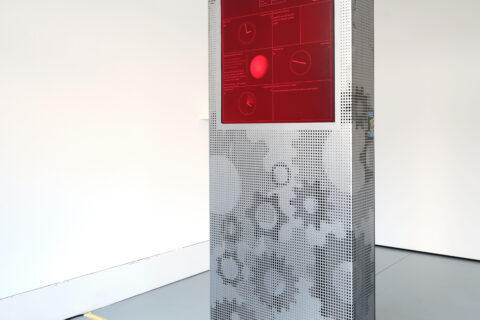

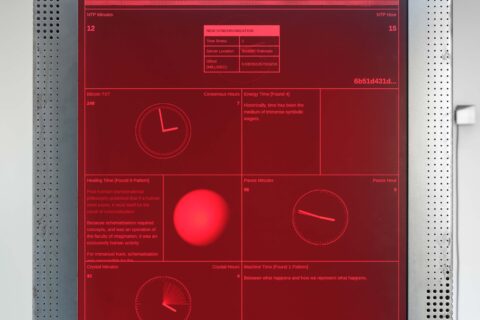

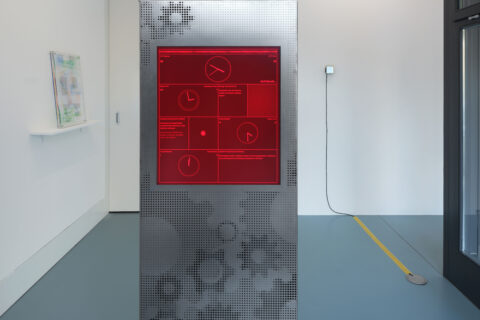

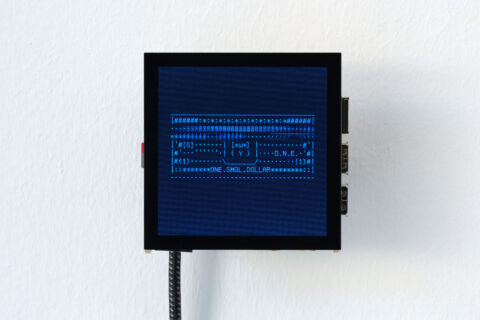

If the value of a commodity is constituted by socially necessary labor time, then the value-form reveals the “socio-historical side of relations.” (Reitter 2011) – and with it, the extent to which the regulation of time is inseparable from the regulation of value. It follows that dominant modes of production seek to institute their own time orders as mechanisms of control over labor and value. In a monolithic terminal reminiscent of public information displays, Temporal Secessionism Timezone 5.5 examines alternative time measurement systems that operate beneath the surface of everyday chronology. The work reveals how networked infrastructures, technical algorithms, and industrial processes produce parallel temporalities – obscured substrates of everyday timekeeping, nevertheless structurally bound to it. Like the previous iterations of Temporal Secessionism, it serves as both an excavation and critique, surfacing the overlapping systems that coordinate and control time within the contemporary regimes of production.

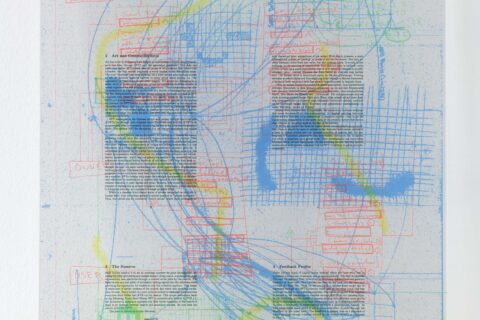

Cipher is arguably Seidler’s most radical response to an ostensibly monopolistic but recently collapsing secondary digital art market on the one hand, and algorithmically curated feeds on the other. ART GOING DARK. Cipher introduces a new type of token, created by the artist, that contains secret metadata stored on the blockchain that is verifiably encrypted using zero-knowledge proofs. The work can be understood as a protocol that is at once an extension and redefinition of the NFT standard. While a standard NFT (ERC-721) can be viewed at any time and is therefore necessarily public, Cipher is private by default – encrypted and only viewable by the owner. Each transfer of the token involves decryption and re-encryption of the metadata, which contains the seed and components of the program code that generates the visual output. The current state of the artwork remains unknowable to outsiders – yet publicly verifiable through zero-knowledge proofs – while remaining accessible to the owner. After a transfer, the respective owner has the option of modifying one of the parameters of the generative visual output, contributing to an ongoing visual lineage and development for each individual work. When, after Broodthaers, artistic theory itself becomes the advertisement of the artist, and when the communication around this is read – in an abridged interpretation – as the real artistic 'surplus value,' then this artwork points toward a generative logic of “refusal to work”. Cipher insists on the primacy of the viewer and the viewing collective. The artwork demands and enforces a specific context of interaction, reproduction, and engagement, collectively developed and hidden from the frictionless logic of the open feed.

Nightmarkets appear wherever the internal contradictions of valorization lead to a divergence between the form of value and the substance of value. It is not itself a revolutionary social form, any more than the market is, but rather manifests itself as a temporary transitional phenomenon toward another mode of production. It arises as a consequence of a crisis logic in which commodities and exchange value are decomposed by the productive forces inscribed in them.

Paul Seidler is an artist, researcher and programmer based in Berlin, whose work traverses networks — from creating decentralized protocols to deploying legal interventions. Since 2015, he has been working with blockchain-based technologies to investigate questions of value, ownership and encryption, thereby creating a body of onchain work using self-written smart contracts, zero-knowledge circuits and token-based protocols. Seidler is recognized as one of the founding members of terra0, a collective comprising developers, theorists, and artists committed to developing hybrid ecosystems within the technosphere. His work has been featured in prominent exhibitions and discussions, including the 7th Athens Biennale, Schinkel Pavilion, Transmediale, the 58th Carnegie International, and KW Institute for Contemporary Art.

- Paul Seidler & Christopher Dake-Outhet

Sources:

Marx, Karl. 1962. Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Erster Band. In: K. Marx/F. Engels, Werke, Band 23. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Reitter, Karl. 2011. Prozesse der Befreiung: Marx, Spinoza und die Bedingungen eines freien Gemeinwesens. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Cras, Sophie. 2018. The Artist as Economist, Art and Capitalism in the 1960s. London: Yale University Press.

Isabelle Graw. 2008. Der große Preis: Kunst zwischen Markt und Celebrity Culture. Freiburg: DuMont Buchverlag.

Lohoff, Ernst. 2020. Auf Selbstzerstörung programmiert: Über den inneren Zusammenhang von Wertkritik und Kriesentheorie in der Marx’schen Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie. Berlin: epubli