John Miller und Dominik Sittig John Miller und Dominik Sittig

05/09/2015 – 30/09/2015

Eröffnung: Freitag, 04. September 2015, 18-22 Uhr

Opening: Friday, September 4th, 2015, 6-10 pm

Galerie Nagel Draxler

An der Schanz 1A

50735 Köln

Öffnungszeiten / Hours:

Tue-Fr: 11 am - 6 pm

Sat: 11 am - 4 pm

Untitled, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

260 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

Untitled, 2015

Acrylic and textile on canvas

260 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

Untitled, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

ø 120 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

Untitled, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

200 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

Installation view, 2015

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne

Photo: Simon Vogel

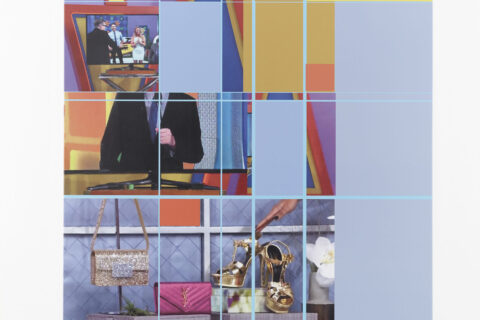

„Informe“, 2015

Dye sublimation printing on polyester fabric

260 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Aporia“, 2015

Dye sublimation printing on polyester fabric

260 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Self-Reflexivity“, 2015

Dye sublimation printing on polyester fabric

200 x 180 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„Incommensurability“, 2015

Dye sublimation printing on polyester fabric

Ø 120 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

Press Release

Malerei als Kritik

Die Ausstellung bringt zwei scheinbar ferne Positionen zusammen.

Den amerikanischen Künstler, Autor und Musiker John Miller (Jahrgang 1954), der seit den 1980er Jahren populäre Phänomene der Gegenwartskultur—altmodisch gesagt —"dekonstruiert", bzw. ihnen in zwischen Pop- und Concept-Art changierenden Bildern, Skulpturen und Installationen nachgeht. Seine Gameshowbilder, die Motive aus amerikanischen Dauerbrenner TV-Shows wie "The Price is Right" aufnehmen, reichen zurück in die 1990er Jahre, in die Zeit, in der die Bedeutung des Fernsehens nach den euphorischen Jahrzehnten der Nachkriegszeit in einem quälenden Prozess der Vertrashung abzunehmen begann. Kritik der Zeit, Kritik der Gesellschaft und Kritik an/in der Kunst spielt Miller in dieser bekannten Serie auf einer einzigen visuellen Ebene aus. Die Bilder bestehen aus gesampelten, direkt vom angehaltenen Screen kopierten Bildausschnitten der Sendungen. Das ödipale Verhältnis zwischen gutem Moderatorenonkel und den Kandidaten, die er in ihrem up and down zwischen kindlicher Hoffnung, Gewinn und Verlust der begehrten Warenobjekte betreut, ist emblematisch für die noch irgendwie mit staatlicher Obhut assoziierte Freie Marktwirtschaft (1). Inzwischen haben sich die Systeme von Kapitalismus und Politik entkoppelt. Während Miller seine Kompositionen anfänglich noch malte und so das Medium der Umsetzung "älter" als das der Vorlage des Bildschirms wirkte, so hat sich bis heute dieses Verhältnis umgekehrt. Die neuen, perfekten Thermosublimationsdrucke auf Polyester glätten eine grobkörnigere Gameshowwelt von Gestern. Pop- und Concept-Art können als originär amerikanische Gattungen angesehen werden, denen Miller hier mit Kritik und Huldigung zugleich gegenübertritt. Die eindeutige "criticality" seiner Arbeiten besteht aber darin, quasi als Kritik der Kritik, deren Historizität erfahrbar zu machen.

Den deutschen Künstler und Autor Dominik Sittig (Jahrgang 1975) trennen rund zwei Generationen und der Atlantik von der Welt John Millers. Seine pastosen Bilder aus gemanschten Acryl- (ehemals Öl-) farbschichten, manche an Stellen mit Gazeknäulen aufgebauscht, könnten auf den ersten Blick für expressive Malereien reinster Natur gehalten werden. Von ihnen geht ein starker Impuls aus, der bei den Betrachtern oft eine Art Widerstand auslöst, welcher auf den gegensätzlichen Schwingungen der Anziehung und Abstoßung beruht. Erst wenn man sich auf die hohe konzeptuelle Ebene der Arbeiten einlässt, erkennt man, dass Sittig nicht den expressiven Ausdruck übt, sondern vielmehr die Kritik des expressiven Ausdrucks durch seine gezielte Inszenierung. Dabei kommt den Bildern ein biografisches Alter zu, das nichts mit Sittigs persönlichem Leben zu tun hat, wohl aber die darin aufgestaute (kunst-)geschichtliche Zeit objektiviert. Der Künstler schreibt in einem seiner Texte, wenn man Kippenberger als Künstler der 1980er Jahre bezeichne, so sei dies nur die halbe Wahrheit. Kippenberger, 1953 geboren, sei ebenso sehr ein Künstler der 1950er, 1960er und 1970er Jahre gewesen. Sittigs Bilder gehen nicht in der Retrogeste auf, die das Informel ironisiert. Seine vielschichtigen Mischmasch-Zitate expressiver europäischer Malereistile üben einerseits Kritik an dem seine geschichtliche Dimension verneinenden abstrakten Ausdruck, welcher - man sieht es heute deutlicher als je zuvor–Ware ist. Andererseits zielen sie auf die Historizität von (Kunst-)Geschichtsbegriffen als solche.

Die beiden Positionen USA / Europa eint eine im Medium der Kunst ausgetragene Kritik der Kritik von Geschichte–und dieser Eindruck entsteht beim Eintritt in den Ausstellungsraum ganz unmittelbar.

--------------------

Painting as critique

This exhibition brings together two seemingly distant positions.

American artist, writer and musician John Miller (born 1954) pursues since the 1980ies (to put it in an old-fashioned way) a kind of "deconstruction" of popular culture, or, maybe more precisely, is reflecting on it in paintings, sculptures and installations that seem to be located in the field of tension between Pop Art and Conceptual Art. His Gameshow paintings that take their subjects from American TV long runners like "The Price is Right" go back to the 1990ies. Thus to a point in time when TV after the euphoria of the post-war years had just begun to enter a long and agonizing period of losing relevance. In this famous ongoing series of paintings Miller plays off the critique of the present, critique of the society, critique of/in art, all on one visual level. The paintings consist of sampled fragments of the broadcasts that are copied directly from the screen. The Oedipal relationship between a good showmaster-uncle type and the participants - he looks after them during their emotional up and down between childish hopes, win and loss of the desired commodity objects, can be regarded as emblematic for a free market economy that is still somehow associated with state care (1). Meanwhile the two systems of capitalism and politics have finally decoupled. While Miller in the beginning painted his compositions and thus made the medium of choice appear "older" than its template on screen, this relation today is reversed. The new thermosublimation prints on polyester smooth the more coarse-grained TV world of yesterday. Pop Art and Concept Art can be regarded as original American genres which Miller confronts with both critique and homage. But the unambiguous "criticality" of his works consists in making their historicality tangible, quasi as critique of critique.

Two generations and the Atlantic Ocean seperate German artist and writer Dominik Sittig from the world of John Miller. Sittig's pastose paintings of meshed layers of acrylic (formerly oil) paint, in some places puffed out with twines of gaze fabric, could be taken as plainly expressive at first sight. The paintings release a pulse that due to the conflicting vibes of attraction and repulsion often evoke a kind of emotional resistance within the observer. Only if one admits to the high conceptual level of the works, one recognizes that Sittig does not practice pure expression, but on the contrary its critique by means of its conscious staging. In this process the paintings gain a kind of biographical age that has nothing to do with Sittig's personal life, but that objectifies the (art-) historical time that it (life) contains. In one of his essays Sittig points out that if one says Kippenberger is an artist of the 1980ies, this only is half the truth. Kippenberger, born in 1953, was as much an artist of the 50ies, 60ies and 70ies. Sittig's paintings are not a retro-gesture that ironically refers to the Informel. His multi-layered mish-mash quotations of expressive European painting on the one hand can be regarded as a critique of the abstract expression that denies its historical dimension and that - this is more obvious than ever - is nothing but commodity. On the other hand this critique focuses on the historicality of (art-) historical conceptions as such.

Both positions USA / Europe share the same critique of the critique of history argued in the medium of art - and this impression emerges instantaneously when entering the exhibition space.

(1) “The quiz show or game show allows for the symbolic circulation of goods within a family that is not a family; it creates a surrogate “family” out of an arbitrary set of contestants, the studio audience, and the (vicarious) broadcast audiences.” John Miller “Playing the Game,” a/drift, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson 1998, p. 93–95; republished as “Das Spiel spielen: Was machen Sie sonntags um zwanzig vor sieben?,” Subtropen/Jungle World, Berlin, no. 32, August 1, 2001, p. 7.