Gang Zhao Hermeneutics and Deconstruction

07/09/2019 – 19/10/2019

Eröffnung: Freitag, 06. September 2019, 18-21 Uhr

Opening: Friday, 06 September, 6– 9pm

Galerie Nagel Draxler

Elisenstraße 4-6

50667 Köln

Öffnungszeiten / Hours:

Mittwoch – Freitag 11–18 Uhr / Wednesday – Friday 11am–6pm

Samstag 11–16 Uhr / Saturday 11am–4pm

DC Open:

Samstag, 7. Sept.: 11–20 Uhr & Sonntag, 8. Sept.: 12–18 Uhr

Saturday, 7th Sept.: 11 am – 8 pm & Sunday, 8th Sept.: 12 pm - 6 pm

GANG ZHAO

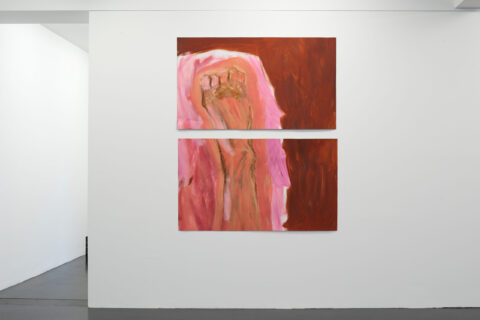

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Hermeneutics and Deconstruction“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

„Chinese Horror“, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

150 x 90 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

“Hermeneutics and Deconstruction”, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

20 Teile in je 155 x 89 cm

Ausstellungsansicht

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Köln

Foto: Simon Vogel

Press Release

August Heat

For Zhao Gang, who was born in the early 60s, and experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand, destruction and revolution seem to be a natural part of his temperament. He was the youngest artist to participate in the “Stars” exhibition, and among the first group of students to go abroad during the Reform Era. Zhao witnessed rapid changes in culture, economics, and politics not only in the West, but around the world. He grappled with seismic shifts in the contemporary art world. These tumultuous experiences have already become a vital part of him. To this day, he still draws on this steady stream of innate destructive and creative power.

The focal point of Zhao Gang’s new exhibition August is a 10 meter long and 3.5 meter wide painting, which was completed August this year. It features a recumbent, full-figured, sleeping nude female. The painting lacks a detailed background, and only offers a hazy outline. Dark brown brushstrokes surround the rough sketch, highlighting the rosy tones of the female body at the center of the painting, and creating the impression of a person nestled in a sealed grotto. As an artist-cum-archaeologist, Zhao Gang uses his own method to hull this mystery buried inside the ground deep in the mountains. The outline of a grotto-like image cleverly echoes the protruding abdomen and chest of the human figure. They both allude to fertility, and build a nested structure. As always, Zhao Gang from start to finish maintains his brutish, wanton, and unpredictable technique of “destructive painting”. Using this style, he emphasizes the voluptuousness and desire of the body in the painting. The painting draws parallels with Manet’s Olympia, in which his depictions of low-class socialites and prostitutes from the streets of Paris served as a response to Titian’s noble and goddess-like Venus of Urbino. Zhao’s painting is also reminiscent of Courbet’s The Source, with the model’s ample flesh and curves in sharp contrast with Ingres’ classically beautiful figures. Based solely on the figure’s headdress and expression, the painting seems to draw inspiration from the ancient sleeping Buddha. Hence in line with Manet and Courbet, Zhao Gang uses a sensual pictorial language to take a sacred figure, and transform them into or attach them onto a prosaic and nameless reality. The entire tableau appears to be an overpowering mirror image, forcing each viewer to reflect on their own inner desire, faith, and destiny.

Yet, it still fails to both satisfy the artist’s urgent need for catharsis, and wash away the restlessness and moodiness brought by the sweltering summer days. Consequently, Zhao Gang made the bold choice to split this complete image into twenty smaller abstract paintings, using repeated destruction to shatter the viewers’ mirror image. In the realm of art history, this technique perhaps returns painting back to its original trajectory. Rather than a representational female nude, we can only see countless brushstrokes and colors amassed into an abstract form. It not only frees the medium from self-sufficiency, but also the painter himself. These abstract fragments no longer bear the burden of any concept, attitude, or mission, and return to a pure “essence of painting.” But Zhao Gang does not want to return to Greenberg’s question. The Dadaist, punk, and anarchist spirit of the painting itself is what actually liberates the artist. Most of the time, his creative processes are fueled by particular reasons or sources, but he often deftly takes these encumbrances, and crushes them into pieces, spraying them into the air. Akin to his work, he would rather transform himself into individual fragments.

In the past few years, he has gotten used to drinking alone in a hidden corner of Timezone 8; used to hauling his Harley out to wander beyond the city borders; used to completely losing his sense of belonging between China and the West, tradition and contemporaneity, and foreign and local—he often calls himself a “bastard”…he has never believed in the concept of “unity”, and is nearly always filled with a sense of prejudice and dissatisfaction with the entire outside world. Nor does he desire that anything become the center of attention, wielding the power to rule or control others. In regards to any type of power, he maintains a degree of suspicion and rebelliousness. You could say that he is a representational painting split into twenty abstract parts, and scattered in all directions. Because he is reluctant to be the center, he is also unwilling to let himself become anyone’s point of focus. Rather than deeming it a de-centralized painting practice, we might see it instead as a dynamic and nomadic self-exile.

– Lu Mingjun

_____

八月流火

对于出生于上世纪60年代初、亲历过文化大革命的赵刚而言,破坏与反叛似乎是与生俱来的气质。他是“星星美展”最年轻的参展艺术家,也是改革开放以来第一批出国游学者,他见证了1980年代以来欧美乃至全球文化、经济及政治的风云变幻,也亲历了当代艺术系统的跌宕起伏……这些已然成了他血液中的一部分,直到今天,依然在激发着他身上源源不断的破坏力和创造力。

新展《八月》的母本是完成于今年8月的一幅长10米、宽3.5米的大画,画面描绘的是一个横卧的、肥硕的沉睡中的裸女。画面没有具体的背景,只是勾勒了一个大致的轮廓,深褐色的笔触布满了轮廓四周,突出了画面中心的粉色调的女性身体。看上去,人物像是窝居在一个封闭的洞穴里,而作为考古学家的艺术家,只是以自己的方式剥开了这个埋藏在地下或深山的秘密。这样一种洞穴般的图式结构巧妙地回应了人物凸起的腹部和胸部,它们都在暗示着孕育,并构成了一个嵌套结构。一如既往,赵刚始终保持着他野蛮、放肆和不拘一格的“坏画”品质,正是这样一种语言风格,更加凸显出画中人物身上粗鄙的肉感和欲望。就像马奈笔下的奥林匹亚一样,他就是要以一个庸俗的巴黎街头的交际花或妓女形象回应提香笔下高贵而神圣的乌比诺的维纳斯;同样是《泉》,库尔贝画中女性的肥臀和赘肉完全不同于安格尔笔下堪称典范的完美形象。赵刚也是,若单从人物的头饰和表情看,其图像母题似乎源自一个古代的睡佛,所以和马奈、库尔贝一样,他也是以粗俗、野蛮的语言方式将这一神圣而不可冒犯的形象转译成或附着在一个庸常的无名的现实形象上。整个画面则仿佛一个压倒性的镜像,逼使每一个观者反视自己内心的欲望、信仰和命运。

然而,这似乎还不能满足艺术家亟需发泄的情绪,还无法彻底冲走夏日炎热带来的焦躁和烦闷。于是,赵刚做了一个大胆的决定,他将这幅完整的具象作品切分为二十张抽象的小画,通过再度破坏将我们每个人内心深处的这个镜像彻底粉碎。如果从艺术史的角度讲,这或许是回到绘画媒介本身的一个途径,因为我们面对的不再是一个具象的裸女,而是无数个纯粹的笔触和颜料堆积的抽象形体。它不仅释放了绘画媒介的自足性,同时也解放了艺术家自我。因为,这些抽象的碎片不再承载任何观念、态度和使命,而是彻底回到了纯粹的“绘画本身”。不过对赵刚而言,重要的显然不是重返格林伯格的命题,真正让他得到解放的是这一绘画举动本身所涵有的达达、朋克的质地和无政府主义精神。大多时候,他都会为自己的创作找到一个绝佳的理由和起因,可结果又常以一种举重若轻方式将这个不堪的理由和起因彻底碾碎,撒向空中,而宁肯将自己化为一个原子化的个体。

这些年来,他已经习惯了一个人躲在“东八”的某个角落自斟自饮,习惯了一个人拖着哈雷浪迹塞外,习惯了一个人往还于中西古今夷夏之间却又始终找不到归属的感觉——他经常称自己是个“杂种”……他从来不相信任何“大一统”的思想,几乎对周遭的一切都充满了偏见和不满,他也不希望某个具体的人或事物占据空间的中心,成为绝对的支配者或宰制者。可以说,对于任何权力,他都保持着警惕和不服从。可以想见,他何以将一张完整的具象画面切分为二十个抽象的局部或片段,散布在空间四周,因为他既不愿成为中心,也不愿自己笼罩在某个焦点之下。而这与其说是一种去中心化的绘画实践,不如说是一次更具能动性和游牧精神的自我放逐。

– 鲁明军

_____

Symbole dienen dem Verstehen. Aber nach welchen Symbolen kann ein Künstler im Jahr 2019 suchen, der sich mit der Zensur der Freiheit des nackten Körpers auseinandersetzt und dabei zwischen asiatischer und westlicher Sicht changiert? Die Frau einmal mehr nackt auf die Leinwand zu bringen, ist erster Schritt der kontinuierlichen Auflehnung gegen ein politisches System, das den 1961 in Beijing, China geborenen Maler Gang Zhao seit jeher begleitet.

Zhao Gang wuchs in China auf, verbrachte dann die 80er und 90er Jahre in New York, bevor er 1997 wieder nach Peking zurückkehrte. Als Künstler mit bilateralem Erbe reflektiert er kanonisierte westliche Positionen aus einer transkulturellen Perspektive. Einerseits spaltet die Hybris der chinesischen Reglementierungen nackte Körperlichkeit in etwas Unnatürliches, Dekadentes, das Konsumierende schlichtweg zu überfordern droht. Auf der anderen Seite herrscht anstelle eines moralischen Zwangs ein ästhetischer. Innerhalb der Reichweite von Facebook gilt „L’Origine du monde“ zwar nicht mehr als unanständig, in der westlichen Kultur sind wir nun jedoch mit der Präsentation des, wie Laura Mulvey es nennt, Perfekten Produkts konfrontiert – der Kastrationsdrohung, dem Fetischobjekt, der Mutter.

Die für die Ausstellung produzierte Arbeit, ein weiblicher Akt im länglichen Großformat, Öl auf Leinwand, wurde von Zhao Gang ursprünglich als Gesamtes gemalt. Im Ausstellungsraum allerdings erscheint das Werk in kleine Stücke zerschnitten auf den Wänden verteilt. Die durchaus ironische Anspielung auf die mediale Zensur in China und das ideologisch verklemmte Pornografie-Verbot der Volksrepublik trägt über nationale Grenzen hinaus. Auch im Titel der Arbeit schwingt ein ironischer Unterton mit. Doch ist das Werk durch die Metapher der Zerstückelung von innen heraus geprägt und strebt so jenseits von Ironie danach, befreiende Konzepte durch den Körper hindurch nach außen zu projizieren. Die Präsentation des Nackten ist immer noch politisch.

Was zumindest zurzeit in China nur bedingt als Cyberrevolution gelingen kann, schafft hier die fragmentierte Leinwand. Thematisch auf Altlasten von kaiserlichen Systemen, ihrer Politik und ihrem Vermächtnis rekurrierend, funktioniert Gang Zhaos Werk als Aufforderung: In dem Blick auf den nackten Körper haben wir die männliche, erotisierende Perspektive auch in Europa nicht vollständig abgelegt. In Hermeneutics and Deconstruction können die Betrachter den eigenen Blick reflektieren und dekonstruieren. Als ständige Zeugen massiver Visualisierung perfekter und ganzheitlicher Körper könnten sie hier lernen, für Details empfänglich zu werden und das Bedeutungsvolle im Segment zu erkennen.

Letztendlich berührt dieser Akt die Selbstwahrnehmung empfindlich, denn hier werden Facetten einer weiten Emotionspalette gespiegelt, die an die Erfahrungen unterdrückter, zensierter, in ihrer Freiheit zerstückelter Frauen und Männer anlehnt.

Museumsausstellungen der letzten Jahre:

"History of Painting“ (noch bis 5. Januar 2020), Pérez Art Museum Miami; "The Road to Serfdom II“ ("Der Weg in die Knechtschaft II“), 2016, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Santiago de Chile; “Paramour’s Garden” („Garten der/des Geliebten“), 2015, Suzhou Museum Suzhou; "The Road to Serfdom“ („Der Weg in die Knechtschaft“), 2015, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Peking.

– Maja Funke

_____

Symbols facilitate understanding. But in 2019, what symbols can an artist, who deals with the censorship of the naked body and whose view is shifting between Eastern and Western perspectives, possibly be looking for? The first step here is to paint the female body naked once again, as an expression of the continuous rebellion against a political system that has been with the artist at all times.

Zhao Gang was born in Beijing in 1961. He grew up in China but spent the 1980s and 1990s in New York, before returning to Beijing in 1997. As an artist with bilateral heritage, he reflects on the Western art canons from a transcultural perspective.

On the one hand the hubris of Chinese regulations divides the naked corporeality into something unnatural and decadent, that simply threatens to overstress the regular consumer. On the other hand, instead of a moral force an aesthetical force comes into action. Within the reach of Facebook „L’Origine du monde“ isn‘t seen as indecent any more, but in Western culture we are now confronted with the Perfect Product – threat of castration, the fetish, the mother, how Laura Mulvey put it.

The work in this exhibition, a large female nude, was originally painted as a whole in oil on canvas. But in the exhibition space it appears cut in small pieces, with the fragments spread over different walls. The slightly ironic allusion to media censorship in China and the uptight ideological ban of pornography works beyond national borders. Also the title of the work has an ironic undertone. But the metaphor of fragmentation respectively dismemberment strongly forms the work from within and beyond all irony. Emancipating concepts are projected through the body to an outside. The presentation of nakedness still is political.

What in a somewhat limited way is succeeding in China today as Cyberrevolution, becomes possible here by means of the fragmented canvas. In recurring to the leftovers of imperial systems, their politics and their legacies, Zhao Gangs new exhibition works as a call: also in Europe, the male eroticized view on the naked body has not been fully set aside. In Hermeneutics and Deconstruction the visitors can reflect and deconstruct their own views. As permanently exposed to the visualization of the perfect and intact body, they can learn to look at details and to discover relevance in each segment.

After all this nude severely touches self-perception. It reflects facets of a wide pallet of emotions, that leans on the experience of oppressed and censored men and women whose freedom is fragmented by power.

Recent museum exhibitions:

"History of Painting“ (until January 5th 2020) Pérez Art Museum Miami; "The Road to Serfdom II“, 2016, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Santiago de Chile; “Paramour’s Garden”, 2015, Suzhou Museum Suzhou; "The Road to Serfdom“, 2015, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing.

– Maja Funke