Zandile Tshabalala Don't Let Me Fall

06/11/2025 – 09/01/2026

Galerie Nagel Draxler

Elisenstraße 4-6

50667 Köln

Opening / Eröffnung:

Donnerstag, 06. November 2025, 18 – 21 Uhr

Thursday, November 6, 2025, 6 – 9 pm

Öffnungszeiten / Opening hours:

Mittwoch - Freitag 11 – 18 Uhr, Samstag 11 – 16 Uhr

Wednesday - Friday 11am – 6pm, Saturday 11am – 4pm

Press Release

“Seduction, however, never belongs to the order of nature, but that of artifice – never to the order of energy, but that of signs and rituals.” (Jean Baudrillard, 1979)

With “Don’t let me fall” Zandile Tshabalala transports us into her cinematic universe of richly detailed scenes imbued with thriving yet fragile joy. Like visual poems, her paintings speak of life moments, flashes of emotional experience to be found in the warm gathering of friends, a mother’s love, the welcoming of a first child, but equally the drowning feelings brought on by mental ill-health. The title of her exhibition is taken from a song in Cleo Sol’s album “Mother” (2021). Lying on a sofa with her baby, Sol sings “Hold me close, please don’t let me go, don’t let me fall…”, a phrase with multiple meanings that echoes the newborn’s murmurs and the mother’s inherent fear of losing or misguiding this precious life, both conditions echoed in Tshabalala’s own experience of motherhood.

Born in Soweto in 1999 to a family of powerful and creative women, ingenious makers and movers of everyday life, Tshabalala is the first in her clan to have become a professional artist. Her trajectory has been remarkable. Beginning with her first solo show at Galerie Nagel Draxler in 2021 (“Beautiful Experiments”), she has become the key protagonist of a new generation of painters based on the African continent and exhibiting internationally. While her meteoric rise began at the highpoint of Black realist portraiture in 2020, her paintings have evolved beyond the canon with an unmissable iconographic and painterly language of their own. Her earlier compositions with their characteristic flat planes and bold use of black, white and red pigment remain but are accentuated today with microscopic multicoloured detail. Glitter boosts the hue of flowers and shades the volume of flesh, while collaged rhinestones trigger flashes of luminosity and give depth to the canvas. Her model women, more often the artist herself, with their deep matte black skin, flash of red nails, and flamboyant costumes emanate soft sensuality and composure, vulnerable only to moments of otherworldly illusion. Tshabalala’s rich pictorial imaginary injects charisma into plants and people alike capturing the metaphysics of our contemporary condition within a decidedly Black aesthetic. Her self-portraits chart her own experience all the while celebrating those girls, sisters and mothers who choose love over despair and act in dialogue with the history of South Africa’s female icons and rebels from singers Dorothy Rathebe to Miriam Makeba, and independent artists Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi and Gladys Mgudlandlu, whom she references in her floral works.

Tshabalala’s artistic world is both erudite and vernacular, stimulated by art-historical references as well as the ubiquitous visual culture of social media. In “Look to the Sky I/II” (2025), a Black female figure floats in a spiralling sea of blue, awash with petals and flourishing pink blooms. This crafted yet haunting imagery veils a complex expressive composition held together by the exquisitely patterned surface of the painting. It recalls Ophelia by English artist and illustrator John Everett Millais from 1851 painted in his iconic Pre-Raphaelite style. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Ophelia who is driven to madness by the murder of her father, enters the water of a lake, and dragged down by the weight of her gown, sinks into oblivion. In Tshabalala’s maelstrom, a woman’s face and limbs float precariouslyover azure waters in a psychic moment that oscillates between life and death. Her diptych captures the dizzying and suffocating effects of invisibility and uncertainty associated with moments of interiorisation and depression.

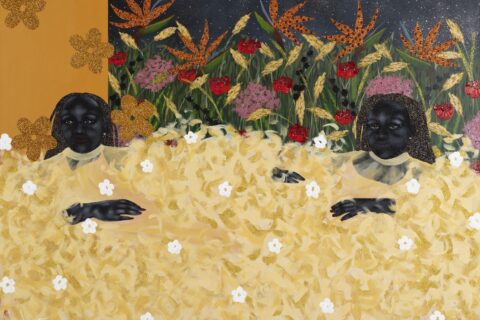

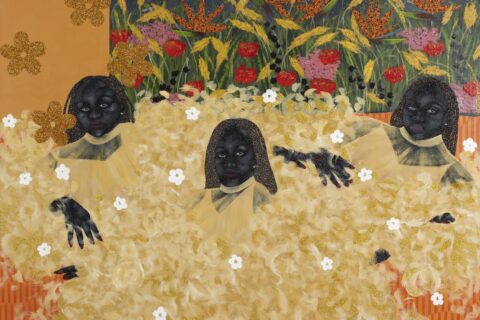

The scene in another diptych “The Invisible Guides” adopts a similar arrangement of background and figure. Three, respectively two, women look out of the canvas, their bodies bathed in flower foam as if smothered by a sea of feathers, lace, and white petals. Clothing hides and protects but is equally a statement of transforming identity and self-affirmation. Tshabalala experiments with the double vision of the diptych format, creating a stereoscopic adjacency that conveys a sense of in betweenness, of movement between situations and states of mind. If city life provides the context for lifestyle and fashion, then photographic archives feature prominently in Tshabalala’s artistic research. Gathered on social media or gleaned from glossy magazines such as early issues of South Africa’s House and Garden, these editorials provide a critical source for the artist with their strange anachronistic images of flower arrangements, interior settings, textures and colour once intended to embellish the modern twentieth century South African home. Leaning on this visual language, and reflecting Dutch flower paintings of the 17th century, she offers us psychotropic bouquets of hydrangeas, chrysanthemums, lilies, parrot flowers, red poppies and yellow corn. Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits come to mind with their floral wallpaper and tropical birds as do the jungle settings of Henri Rousseau “Le Douanier”, the sirens and mermaids in West African Mami Wata paintings, and the decorative portrait photography of Seydou Keïta that blends the sitter’s clothes with the studio backdrop.

Tshabalala skilfully rids these references of nostalgia and through her “strategy of appearances” (Baudrillard) offers us the polyvalence of situations in the here and now, such as the moment when her figure picks up a white gerbia and, looking back at the viewer, thinks, “Joy comes in the morning”. In this masterly conspiracy of signs, in which text and floral combine with skin and dawn skies, Tshabalala proves once again that her figuration challenges our appreciation of both painting and subject matter. She invites us to enter the intimate space of her paintings in which the Black female figure is at home.

Clémentine Deliss, October 2025