Gruppenausstellung – konzipiert von Dominik Sittig AT THE LOOSE ENDS OF THE LOSS

07/06/2018 – 08/09/2018

Eröffnung: Mittwoch, 6. Juni 2018, 18 – 21 Uhr

Opening: Wednesday, June 6, 2018, 6 – 9 pm

Nagel Draxler Kabinett

Rosa-Luxemburg-Str. 33

10178 Berlin

Öffnungszeiten / Hours:

Dienstag – Samstag: 11 – 18 Uhr / Tuesday – Saturday: 11 am – 6 pm

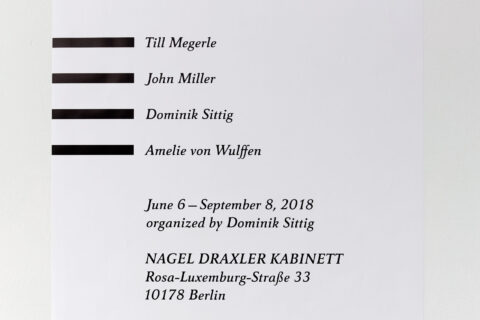

Ausstellungsposter

„AT THE LOOSE ENDS OF THE LOSS“

Photo: Simon Vogel

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

– konzipiert von Dominik Sittig

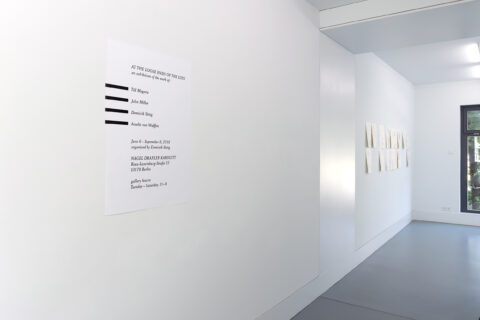

Ausstellungsansicht, 2018

Nagel Draxler Kabinett, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

– konzipiert von Dominik Sittig

Ausstellungsansicht, 2018

Nagel Draxler Kabinett, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

– konzipiert von Dominik Sittig

Ausstellungsansicht, 2018

Nagel Draxler Kabinett, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

Aus der Serie: „The Middle of the Day“, seit 1994

Inkjet prints

je 21,6 x 27,9 cm

John Miller

Ohne Titel, 2017

10 Tassen

Unikat

Photo: Simon Vogel

Ohne Titel, 2017

10 Tassen

Unikat

Photo: Simon Vogel

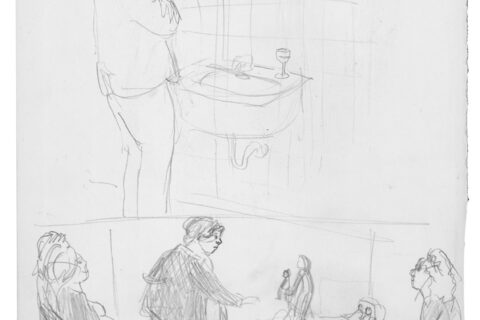

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

– konzipiert von Dominik Sittig

Ausstellungsansicht, 2018

Nagel Draxler Kabinett, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

– konzipiert von Dominik Sittig

Ausstellungsansicht, 2018

Nagel Draxler Kabinett, Berlin

Photo: Simon Vogel

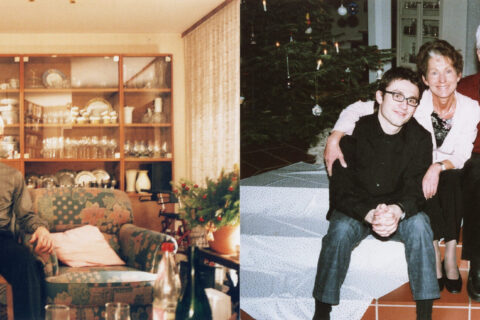

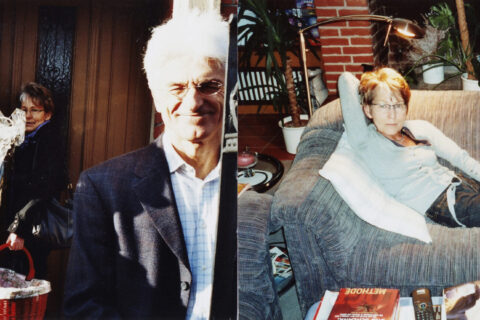

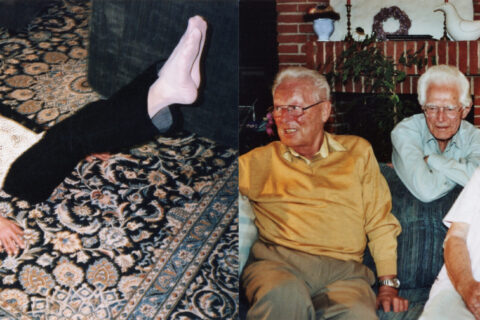

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

je 29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Photo: Simon Vogel

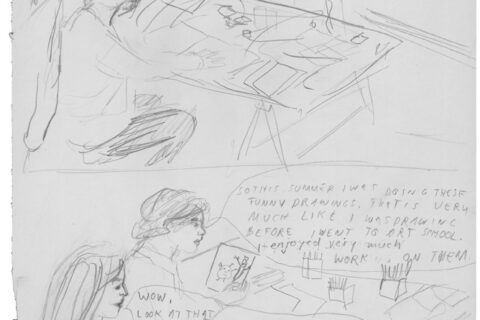

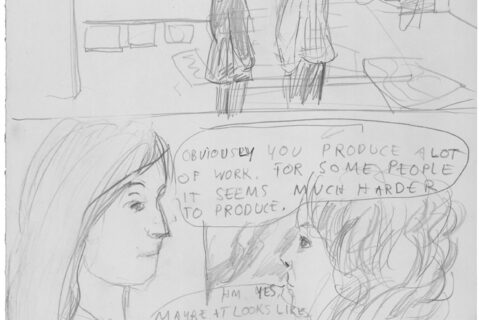

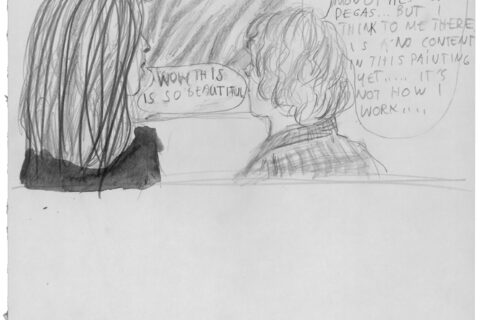

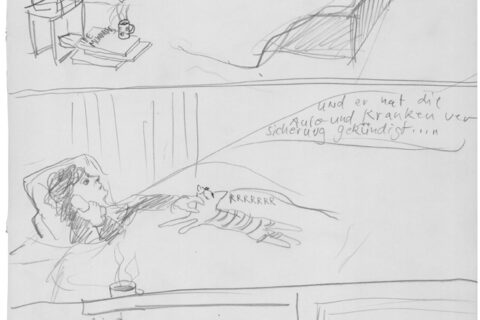

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

Photo: Simon Vogel

„AT THE LOOSE ENDS OF THE LOSS“

Photo: Simon Vogel

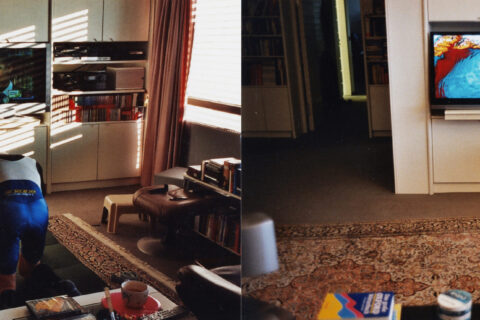

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

Aus der Serie: “The Middle of the Day”, since 1994

Inkjet print

21,6 x 27,9 cm

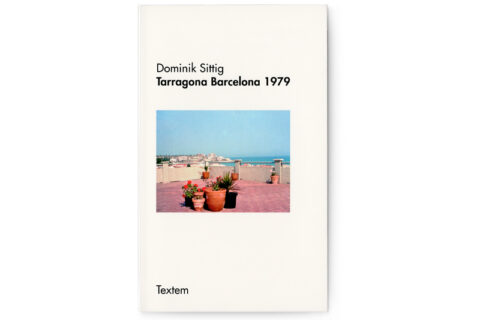

„Tarragona Barcelona 1979“

Textem Verlag, Hamburg, 2015

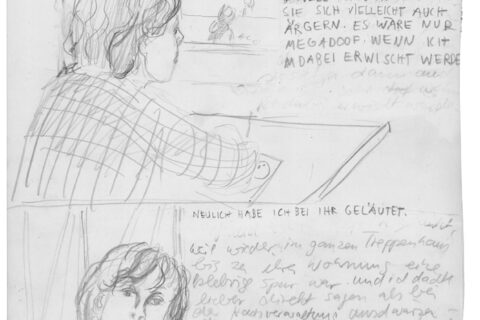

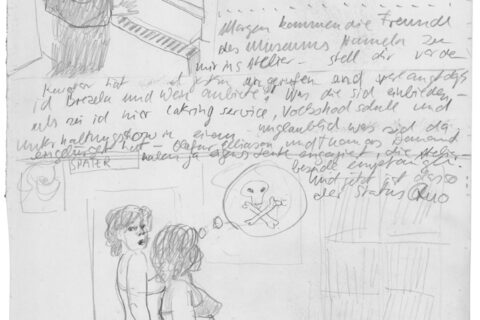

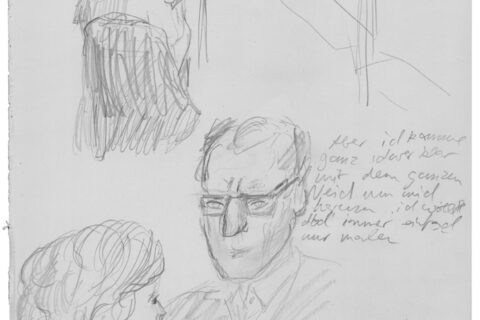

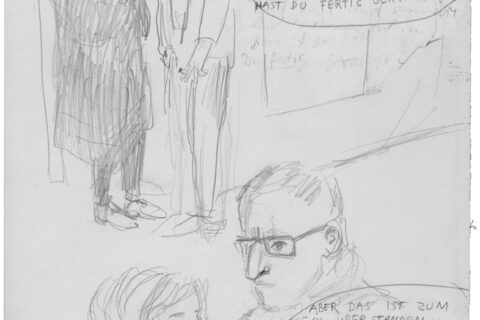

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

„November“, 2011

Ausschnitt aus einer 64-teiligen Arbeit

Bleistift auf Papier

je 35,2 x 26,8 cm

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Aus der Serie: „Baireuth“, seit 2003

Fotografien

29 x 36 cm (gerahmt)

Press Release

Till Megerle, John Miller, Dominik Sittig, Amelie von Wulffen

Ausgangspunkt für diese Ausstellung ist die Form des Tagebuchs als künstlerisches Genre. Gerade in der bildenden Kunst ist diese Form aber nicht auf das Medium Buch und den geschriebenen Text beschränkt: Wie die Schrift so stellen auch Fotografie und Zeichnung (Film oder Malerei wären ebenso denkbar) Möglichkeiten der „Notation“ dar.

Woher kommt dieser Wunsch, sogar manchmal ganz plötzlich, ein Tagebuch zu schreiben? Oder etwas zu beginnen, das dem klassischen Tagebuch zumindest in den beiden Punkten des Aufzeichnens und der Chronologie vergleichbar ist? Dieser Wunsch, alltäglichen Erfahrungen, die an sich nichts Besonderes sind und die vielleicht viele machen, eine dokumentierende Form zu geben? Eine Form, die nicht versucht, all die Banalitäten und das Ephemere daran als mehr erscheinen zu lassen, als sie sind, aber auch nicht als weniger, nicht als etwas Überflüssiges, das zuletzt nur für einen selbst interessant ist, sondern als etwas, das sich eben nicht in bloßer Selbstbespiegelung gefällt? – „Aber bitte! Was ist denn ein Tagebuch sonst?!“

Einar Schleef greift zur Veranschaulichung seiner Auffassung auf einen Archetyp des antiken Theaters zurück: Für ihn ist das Tagebuch als Form der klassische Monolog, die existenzielle Klage des Einzelnen gegenüber dem Gesang des Chors. Eine Klage, in der das Individuum sein Ich überhaupt erst zu formen beginnt, indem es sich von den Übrigen, den „Pestkranken, Hungrigen“, trennt. Zugleich ist diese Klage ein Nichts – ohne das Gegenüber und die Antwort des Chors.

Aber das Tagebuch ist nicht nur die Plattform, auf der ein einzelnes Ich sich ausagiert. Auch nicht bei Schleef. In seinem Text Kontainer Berlin nennt er sein Tagebuch auch eine „Sittengeschichte, die teilweise Ostsittliches festhält, das sich heute nur noch als Schlacke erweist.“

Das Tagebuch ist immer auch Zeitdokument: ein Pool, der in sich – wie mit dem Kescher oder einem Netz oder Sieb, das die Autorin ist – Treibgut, Blätter und Partikel sammelt, aus denen dann rückwirkend dieses Bild sich ergibt, das man üblicherweise „Vergangenheit“, aber eben noch nicht „Geschichte“ nennt.

Denn das konservative Begehren, das Chroniken als Formen der Geschichtsschreibung meist charakterisiert und das mit aller Konsequenz Festhalten und Überliefern will, geht im künstlerischen Tagebuch vom Material (den Geschehnissen und Eindrücken) auf die Form über, wird ästhetisch und erratisch – vermutlich in dem Gespür, dass das, was man doch so sehr bewahrt sehen möchte, das Leben, als solches einfach nicht konservierbar ist.

Das Tagebuch konstruiert Wirklichkeit, wie auch jedes einzelne Gehirn andauernd Wirklichkeit für sich konstruiert, konstruieren muss, um „Wirklichkeit“ überhaupt wahrzunehmen. Aber auf der Ebene des Tagebuchs wird diese singuläre subjektive Konstruktion (samt ihren Fehlern, Vorurteilen und Einbildungen) wenigstens in Ansätzen einsehbar und nachvollziehbar und öffnet sich damit den Übrigen, dem „Chor“. Das Tagebuch ist immer auch ein Angebot des Einzelnen: sein Bemühen um Auseinandersetzung und Austausch. Das Problem heute ist (aber vielleicht war das nie anders): Wo – und vor allem: Wer ist der Chor?

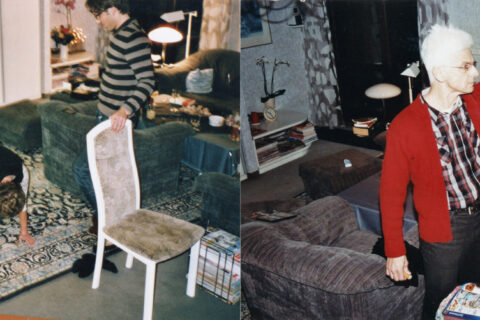

In seiner fotografischen Serie mit dem Titel BAIREUTH dokumentiert Till Megerle (Jg. 1979) seit bald mehr als 15 Jahren Augenblicke und Ereignisse im Leben seiner Familie in Bayreuth. Neben den Eltern, Großeltern und dem Bruder ist es immer auch die sie umgebende Szenerie, die Megerle wichtig ist: das Haus, seine Zimmer und Inneneinrichtungen, das Wohnviertel am Stadtrand, in dem es sich befindet, die typischen Vorgärten, Ein- und Mehrfamilienhäuser, Bungalows und Garagenhöfe. Die einzelnen Aufnahmen werden in der Serie in Form von kleinen gerahmten Diptychen präsentiert, die in ihrer bewusst nicht chronologischen Zusammenstellung und Abfolge das Fremde und Befremdliche als Teil des Vertrauten und Geliebten aufscheinen lassen, ohne die Menschen dabei in ihren Alltäglichkeiten oder auch Eigenartigkeiten bloßzustellen.

John Miller (Jg. 1954) wirkt dagegen eher wie der Benjaminsche Flaneur, wenn er in seiner Fotoserie THE MIDDLE OF THE DAY zumeist Situationen und Passanten im urbanen Raum wiedergibt (obwohl es auch Stillleben und Interieuraufnahmen gibt). Der Titel und das Konzept, nur zwischen 12 und 14 Uhr zu fotografieren, ergab sich aus der anfänglichen Idee, gerade dann mit der Kamera auf Tour zu gehen, wenn die Sonne in ihrem Zenit steht – was unter Fotografen wegen der Lichtverhältnisse als eher ungünstige Voraussetzung gilt. Dass dem gar nicht so sein muss, beweist Miller mit seiner seit 1994 bis heute fortlaufenden Serie, in der Eindrücke und Stimmungen aus aller Welt zu einer Art von mittäglichem Kaleidoskop verbunden sind.

TARRAGONA BARCELONA 1979 geht auf ein zunächst formloses Traumtagebuch zurück, das ich ungefähr ein Jahr lang (2012 bis 2013) geführt habe. Die Publikation setzt sich schließlich aus drei verschiedenen Teilen zusammen: aus einer Fotostrecke von Schnappschüssen aus einem Urlaub in den späten 70er Jahren, durch deren Auswahl und Anordnung ein gewissermaßen ideales Erinnerungsbild sich ergibt, aus Insert-artig eingefügten Artikeln, die der Tagespresse des Jahres 2012/13 entnommen wurden, und eben den literarisch überarbeiteten Traumnotationen, in denen Erinnerungen an Kindheit und Familie und die aktuell erlebte Gegenwart (in Gestalt auch ihrer Protagonisten aus dem Kunstkontext) sich traumtypisch durchdringen.

Ebenfalls traum- und tagebuchartig funktionieren die Bilder- oder Comic-Geschichten NOVEMBER und AM KÜHLEN TISCH von Amelie von Wulffen (Jg. 1966). In mal mehr, mal weniger zusammenhängenden Bilderfolgen verwischt von Wulffen allerdings die Grenze zwischen tatsächlich erlebten Begebenheiten und fiktiven Elementen, indem sie ihr Comic-Alter- Ego (einschließlich seiner Fantasien, Wünsche und Ängste) von Anfang an als exemplarische Figur anlegt, die stellvertretend (für alle) das Alltagsleben einer Künstlerin zu bewältigen hat. Was sonst in den Gemälden nur übersetzt und in der Mehrdeutigkeit des jeweiligen Bildes seinen Ausdruck findet, kommt hier scheinbar skizzenhaft unmittelbar zur Sprache: die fast schon schmerzlich empfundenen Abhängigkeiten von den jeweiligen sozialen Netzwerken, die Ängste vor ihrem Verlust und dem Ausgegrenzt-Werden, der Neid auf vermeintlich Erfolgreichere als man selbst, die zeitweilige Ausweglosigkeit und Unsicherheit im Kunstmachen, wenn man nicht weiß, wie und wo es weitergehen soll. Wenn es bei all diesen existenziellen Fragen und Sorgen keineswegs larmoyant zugeht, liegt das vor allem an von Wulffens trockenem und „kühlem“ Humor, der wie aus der Verzwicktheit der Probleme selbst gewonnen scheint.

Dominik Sittig

Zitate aus: Einar Schleef, Tagebuch 1999-2001. Berlin * Wien, Frankfurt am Main 2009, 1.Aufl., S. 413ff

_______________________________

The starting point for this exhibition is the diary form as artistic genre. In the visual arts, this form is no longer limited to the medium of the book or the written word: Photography and drawing (and, potentially, film and painting too) can, like writing, also represent a form of “notation.”

Where does our—sometimes urgent—desire to start a diary come from? Or at least to begin something comparable to the classic diary format, by recording things in a chronological way? This desire to document everyday experiences that, in themselves, are not particularly important and are potentially experienced by many other people? A form that does not attempt to present banalities and ephemera as more than they are, but also not less than they are; not as something superfluous that is only of interest to oneself, but also as something that does not fall into the trap of mere navel-gazing?—“Oh, come on! What else is a diary for?!”

In his own conception of the diary, Einar Schleef draws on archetypes of ancient Greek and Roman theatre. He sees the diary as a form of classical monologue, the existential lament of the individual set against the song of the chorus. A lament in which the individual begins to form their own ego for the very first time, by distinguishing themselves from others, from the “plague-ridden, the hungry.” And yet this lament does not exist without the opposition and response of the chorus.

But the diary is not only the platform on which an individual ego has room to express itself. Nor does Schleef understand it this way. In his text Kontainer Berlin he also describes his diary as a “history of customs and norms, which in part records the mores of East Germany, which today prove to be nothing but trash.”

A diary is always simultaneously a historical document: A pool which—like with a ladle or a net or a sieve, which the author is—collects flotsam, leaves, and particles, which are used retrospectively to form an image that we call “the past,” but not yet “history.”

Because the conservative desire—which the chronicle as a form of historical writing generally characterizes and desperately attempts to both capture and record for posterity—shifts, in the case of the artistic diary, from the material (the happenings and impressions) to the form, becoming aesthetic and erratic—sensing, perhaps, that the thing that one wants to preserve so much—life—is essentially ephemeral.

The diary constructs reality in the same way that every brain is constantly constructing its own reality, must construct it, in fact, in order to perceive “reality” at all. On the level of the diary, though, this singularly subjective construction (with its errors, prejudices, and conceits) is at least visible and comprehensible and thus opens itself up to the others, to the “chorus.” The diary is always also an offering from the individual: Their attempts at confrontation and discourse. The problem today (and perhaps always) is: Where is and—most importantly—who is the chorus?

In the photographic series BAIREUTH, the artist Till Megerle (b. 1979) has documented events and moments in the lives of his family in Bayreuth for over 15 years. Alongside his parents, grandparents and brother, Megerle’s focus is also always on their surroundings: The house, its rooms, their fixtures and fittings, the suburban estate on the edge of the city, with its typical front gardens, houses and apartment blocks, bungalows and rows of garages. The individual pictures in the series are presented in the form of small, framed diptychs, which are intentionally arranged and sequenced unchronologically, thus showing that the strange and disconcerting is always part of the intimate and loved, without ever belittling the subjects in their ordinariness and idiosyncrasy.

John Miller (b. 1954) takes up the role of the Benjaminian flaneur in his photographic series THE MIDDLE OF THE DAY, generally depicting situations and passers-by in urban spaces (though he also photographs still-lives and interiors). The title of the work and the concept of only taking photographs between midday and 2 p.m. originated from the idea of wandering around with his camera when the sun was at its zenith—a time many photographers consider to be unfavorable for taking photographs because of the light conditions. With this ongoing series, begun in 1994, Miller proves the opposite is true in pictures in which impressions and moods from around the world are connected in a kind of noontime kaleidoscope.

TARRAGONA BARCELONA 1979 draws on an informal dream diary that I kept for about a year (2012 to 2013). The final publication was put together from three different parts: A sort of idealized visual souvenir created from the selection and arrangement of a series of snapshots from a holiday in the late 1970s; inserted articles taken from the daily press between 2012 and 2013; and the revised dream notes, in which, as is typical of dreams, memories of childhood and family pervade the experienced present (including its protagonists in the art world).

The comic stories NOVEMBER and AM KÜHLEN TISCH (At the Cool Table) by Amelie von Wulffen (b. 1966) are also both dreamlike and diaristic. In sequences of pictures, some more linked than others, von Wullfen blurs the boundaries between real experienced incidents and fictive elements. She does so by making her comic alter ego (as well its fantasies, desires, and fears) into a paradigm that must vicariously deal (for everyone) with the everyday life of an artist. Things that, in the paintings, are normally expressed only in translation and in the ambiguity of the picture in question are here given sketchy and immediate voice: The almost painful interdependence of specific social networks; the fear of losing them and being sidelined from them; envy of people who appear more successful than oneself; the sporadic hopelessness and insecurity of making art when you do not know how to keep going and in which direction. If these existential questions and concerns do not come across as lachrymose in any way, it is down to von Wulffen’s dry and “cool” humor, which itself seems to be drawn from the complexity of these problems.

Dominik Sittig

Translation: Ben Fergusson

Quotation: Einar Schleef, Tagebuch 1999–2001. Berlin * Wien, Wien, Frankfurt am Main, 2009, 1st edition, pp. 413ff